Don't Stutter When Talking but Stutter When Reading Aloud

Why you should read this out loud

Most adults retreat into a personal, placidity world within their heads when they are reading, but we may be missing out on some vital benefits when we do this.

F

For much of history, reading was a adequately noisy activity. On dirt tablets written in ancient Iraq and Syria some 4,000 years ago, the commonly used words for "to read" literally meant "to cry out" or "to listen". "I am sending a very urgent message," says 1 letter from this menstruum. "Heed to this tablet. If information technology is advisable, have the king heed to it."

Only occasionally, a different technique was mentioned: to "see" a tablet – to read information technology silently.

Today, silent reading is the norm. The majority of us canteen the words in our heads as if sitting in the hushful confines of a library. Reading out loud is largely reserved for bedtime stories and performances.

But a growing body of research suggests that we may be missing out by reading just with the voices inside our minds. The ancient art of reading aloud has a number of benefits for adults, from helping improve our memories and understand complex texts, to strengthening emotional bonds between people. And far from being a rare or bygone action, it is still surprisingly mutual in modern life. Many of us intuitively use it as a user-friendly tool for making sense of the written word, and are merely not aware of it.

Colin MacLeod, a psychologist at the University of Waterloo in Canada, has extensively researched the impact of reading aloud on memory. He and his collaborators have shown that people consistently recall words and texts ameliorate if they read them aloud than if they read them silently. This retentivity-boosting effect of reading aloud is particularly potent in children, but it works for older people, too. "Information technology'southward beneficial throughout the historic period range," he says.

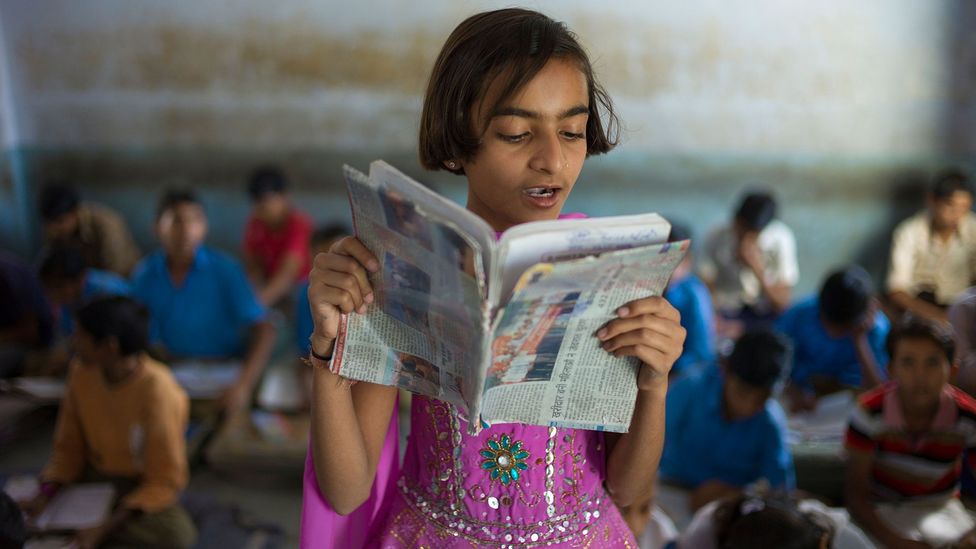

Reading aloud is often encouraged in school classrooms, but about adults tend to do most of their reading silently (Credit: Alamy)

MacLeod has named this phenomenon the "production effect". Information technology means that producing written words – that's to say, reading them out loud – improves our retention of them.

The production effect has been replicated in numerous studies spanning more than a decade. In one study in Commonwealth of australia, a group of 7-to-10-twelvemonth-olds were presented with a list of words and asked to read some silently, and others aloud. Afterwards, they correctly recognised 87% of the words they'd read aloud, but only 70% of the silent ones.

In another report, adults aged 67 to 88 were given the same task – reading words either silently or aloud – earlier then writing downwardly all those they could remember. They were able to recall 27% of the words they had read aloud, simply just 10% of those they'd read silently. When asked which ones they recognised, they were able to correctly place eighty% of the words they had read aloud, but only 60% of the silent ones. MacLeod and his squad have constitute the effect can last up to a week afterward the reading task.

Yous might as well like:

- Can y'all read at superhuman speeds?

- How your language limits your senses

- Why reading fiction might make you a better person

Even just silently mouthing the words makes them more memorable, though to a lesser extent. Researchers at Ariel University in the occupied West Banking company discovered that the retention-enhancing effect also works if the readers take speech difficulties, and cannot fully articulate the words they read aloud.

MacLeod says one reason why people remember the spoken words is that "they stand out, they're distinctive, because they were done aloud, and this gives y'all an additional footing for retentivity".

We are generally better at recalling distinct, unusual events, and also, events that require active involvement. For instance, generating a discussion in response to a question makes it more than memorable, a phenomenon known as the generation result. Similarly, if someone prompts you lot with the clue "a tiny infant, sleeps in a cradle, begins with b", and you respond infant, you're going to think information technology better than if you lot simply read it, MacLeod says.

Another way of making words stick is to enact them, for instance by billowy a ball (or imagining bouncing a ball) while saying "bounciness a ball". This is chosen the enactment outcome. Both of these effects are closely related to the product effect: they let our retentiveness to associate the word with a distinct event, and thereby make it easier to retrieve afterward.

The production effect is strongest if we read aloud ourselves. Merely listening to someone else read tin can benefit retentivity in other ways. In a study led by researchers at the Academy of Perugia in Italy, students read extracts from novels to a group of elderly people with dementia over a total of lx sessions. The listeners performed better in memory tests afterward the sessions than before, possibly because the stories made them draw on their ain memories and imagination, and helped them sort past experiences into sequences. "It seems that actively listening to a story leads to more intense and deeper information processing," the researchers concluded.

Many religious texts and prayers are recited out loud as a way of underlining their importance (Credit: Alamy)

Reading aloud can likewise make certain memory issues more obvious, and could be helpful in detecting such issues early on. In one report, people with early on Alzheimer's affliction were found to exist more likely than others to make certain errors when reading aloud.

There is some evidence that many of us are intuitively aware of the benefits of reading aloud, and apply the technique more than we might realise.

Sam Duncan, an adult literacy researcher at University College London, conducted a two-year study of more than 500 people all over Britain during 2017-2019 to detect out if, when and how they read aloud. Often, her participants would get-go out by saying they didn't read aloud – but then realised that actually, they did.

"Developed reading aloud is widespread," she says. "It'due south non something we but practice with children, or something that only happened in the past."

Some said they read out funny emails or messages to entertain others. Others read aloud prayers and blessings for spiritual reasons. Writers and translators read drafts to themselves to hear the rhythm and flow. People also read aloud to make sense of recipes, contracts and densely written texts.

"Some find it helps them unpack complicated, difficult texts, whether information technology'south legal, academic, or Ikea-style instructions," Duncan says. "Mayhap information technology's about slowing downward, maxim it and hearing information technology."

For many respondents, reading aloud brought joy, comfort and a sense of belonging. Some read to friends who were sick or dying, as "a mode of escaping together somewhere", Duncan says. One woman recalled her female parent reading poems to her, and talking to her, in Welsh. After her mother died, the woman began reading Welsh poetry aloud to recreate those shared moments. A Tamil speaker living in London said he read Christian texts in Tamil to his wife. On Shetland, a poet read aloud poetry in the local dialect to herself and others.

"There were participants who talked near how when someone is reading aloud to you, yous feel a flake like you're given a gift of their time, of their attention, of their voice," Duncan recalls. "We meet this in the reading to children, that sense of closeness and bonding, simply I don't think we talk near it as much with adults."

If reading aloud delivers such benefits, why did humans ever switch to silent reading? 1 clue may prevarication in those dirt tablets from the aboriginal Near East, written by professional scribes in a script called cuneiform.

Many of us read aloud far more than often in our daily lives than we perhaps realise (Credit: Alamy)

Over time, the scribes adult an ever faster and more than efficient way of writing this script. Such fast scribbling has a crucial advantage, according to Karenleigh Overmann, a cerebral archaeologist at the University of Bergen, Norway who studies how writing affected human brains and behaviour in the past. "Information technology keeps up with the speed of thought much meliorate," she says.

Reading aloud, on the other hand, is relatively slow due to the extra footstep of producing a audio.

"The ability to read silently, while bars to highly proficient scribes, would accept had singled-out advantages, peculiarly, speed," says Overmann. "Reading aloud is a behaviour that would irksome down your power to read rapidly."

In his book on aboriginal literacy, Reading and Writing in Babylon, the French assyriologist Dominique Charpin quotes a letter by a scribe called Hulalum that hints at silent reading in a hurry. Evidently, Hulalum switched betwixt "seeing" (ie, silent reading) and "saying/listening" (loud reading), depending on the state of affairs. In his letter of the alphabet, he writes that he cracked open a dirt envelope – Mesopotamian tablets came encased within a sparse casing of dirt to prevent prying eyes from reading them – thinking it contained a tablet for the king.

"I saw that it was written to [someone else] and therefore did not have the king mind to it," writes Hulalum.

Peradventure the aboriginal scribes, only like united states today, enjoyed having two reading modes at their disposal: one fast, user-friendly, silent and personal; the other slower, noisier, and at times more memorable.

In a time when our interactions with others and the barrage of information we take in are all besides transient, perhaps it is worth making a bit more than time for reading out loud. Perhaps yous even gave it a try with this article, and enjoyed hearing it in your own vocalization?

Correction: An earlier version of this article identified Ariel Academy every bit beingness in Israel, when information technology is in occupied territory in the Due west Bank. We regret the error.

--

Bring together one million Future fans past liking us on Facebook , or follow usa on Twitter or Instagram .

If you liked this story, sign upwards for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called "The Essential Listing". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future , Civilisation , Worklife , and Travel , delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200917-the-surprising-power-of-reading-aloud

0 Response to "Don't Stutter When Talking but Stutter When Reading Aloud"

Post a Comment